The Dreaded H-Word

Should Labors of Love be Tax-Deductible?

“A hobby loss refers to any loss incurred while a taxpayer conducts business that the IRS considers a hobby. The IRS defines a hobby as any activity undertaken for pleasure rather than for profit.”- Investopedia

“We need to talk about your podcast.” Thus read the email from my accountant, Miles, in reference to my 2022 tax return.

Whether you hear it from your CPA, lawyer, or lover, “We need to talk” means that bad news is coming. This was no exception, as the remainder of his note explained: “I’m concerned that the significant deductions from podcast-related expenses will trigger an IRS audit, due to the Hobby Loss Rule.”

Yikes. The threat of an IRS audit is nothing to take lightly. I’ve been audited before and, while I came out squeaky clean, the process required in-depth forensic homework and consumed weeks of my life. It’s not an experience I want to repeat.

But as scary as a lube-free government probe might be, the word in his note that caught my eye and turned my stomach was not The A-word; it was The H-word. He was calling my podcast a “hobby,” and—as pathetic as it feels to admit this—it hurt my feelings. Like, a lot.

The IRS Hobby Loss Rules rightfully exist to prevent rich dudes from, for example, buying a ranch and then using its significant, vacation-like expenses to reduce their taxable income. It’s a fair policy, but words matter and, according to Wikipedia, “hobby” is a “pejorative term” for someone engaged in a “childish pursuit.” To the IRS, one’s side—or sole—hustle is legitimate only if it generates revenue. If it does not, then that person is a drooling, navel-gazing dilettante dabbling in a masturbatory vanity project. At least that’s how I read it.

Interpreted through the lens of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, Miles’ counsel was dead on—my tens of thousands of dollars in 2022 podcast expenses were way out of proportion to the associated revenue, which equaled…what was the exact sum? Oh yes – zero.

But evaluated through the lens of my fragile ego, my podcast is most definitely not a hobby. Over the past five years, I have recorded 200 interviews with people like LL COOL J, Judd Apatow, Ryan Holiday, Andrew Yang, and winners of the Nobel Prize, Heisman Trophy, PGA Championship, and Olympic gold medals. I have more than held my own in conversations with best-selling authors, philosophers, CEOs, university presidents, billionaires, and a member of the House of Lords. Third-party metrics indicate that my audience is in the top .5 percentile of all podcasts worldwide, and people I have never met seek me out to tell me that my work has made them better human beings.

Does that sound like a fucking hobby?

Well, according to the IRS, yes, that’s precisely what it is, regardless of how deeply their opinion wounds my pride. Speaking of which, my visceral reaction to their bureaucratic diagnosis warranted reflection as to why I was taking this so personally. I think it’s because I’ve invested so much in my podcast, Crazy Money, both financially and emotionally.

Anyone with a smartphone can make a podcast, but the low barriers to entry disguise an ugly truth: producing a decent show is hard and very expensive. On top of recording equipment and software subscriptions, I spend a few hundred bucks per episode for audio editing, which doesn’t seem terrible until you multiply it by 40 episodes per year. And there’s no upper limit on how much one could spend on guest bookers, publicists, and social media managers, to say nothing of video production without which you’ll miss the growing audiences on YouTube and Spotify and non-optional promotional clips for Insta, TikTok, and Snapchat. But even if you put together a fantastic product and invest loads in marketing, your chances of breaking through the clutter are meager.

On a recent episode of the Pivot podcast, Scott Galloway shared with co-host Kara Swisher the harsh financial realities of the 3-million-show podcast universe, saying “Anything outside of the top 300-500 podcasts are just marketing or hobbies.” (Yes, he used that word.) Even with the backing of a massive platform like Spotify, A-List celebrities like the Obamas and the Sussexes couldn’t make “the juice worth the squeeze,” which helps to explain the recent spate of industry layoffs and why the number of net new podcasts is flat or down.

Galloway, who once described indie producers like me as “wannabe Joe Rogan’s,”* went on to tell Swisher that podcasting makes no sense for the creator unless he or she is deriving a lot of “psychic income.” My ears perked up. Here was one of those moments of illumination that come when you listen to brilliant people engaged in the kind of long-form, constraint-free conversations you only get on podcasts.

While discussing the potential profit or loss Sirius would incur from its new deal with Smartless, Grumpy Prof G dropped some knowledge that struck home. The reason I persevere, despite the massive time commitment and dogshit economics, is because producing my show makes me feel engaged and useful. I learn a lot. I meet incredible people. I provide value for my small but very real audience of curious listeners who often tell me my work matters—that I matter. That’s why I take it personally.

More to the point, Crazy Money is a big part of what I’ve done with my life over the past half-decade. In addition to being a committed husband, loving father, and pretty good stand-up comic, it’s who I am. Lacking a professional title at a recognizable institution, I am “Paul Ollinger, comedian and podcaster.” Don’t you see that, IRS?

When I left my job at Facebook, I tried to articulate to a friend my frustrations with the role-playing that is required in the corporate world, saying “I’m just trying to find work that feels like me being me.” And I’ve found it. The only downside is that it hasn’t paid so great, yet.

I have been asked, “How do you figure out what to do with yourself when you no longer need a paycheck?” Here’s my answer, “Ask yourself: what are you willing to spend several years learning to do with no expectation of financial compensation?”

Perhaps it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. If there are no barriers to entry for a field that pays significant psychic income, then supply will always exceed demand, profits will be non-existent, and—even if you’re in the top .5 percentile of your chosen field—there will be thousands of others between you and the leaders in your category.

These market conditions might prevent me and my fellow podcasters from ever reaching that orgasmic intersection of the authentic and the lucrative, although I have managed to reduce my burn rate. In 2023, I scraped my way to mid-five figures in speaking fees and Substack subscriptions. (Thank you, kind readers!) It’s still a money pit, but it’s slightly less deep.

The good news is that I still love it. And unlike a paycheck, psychic income is not taxable. At least not yet. So don’t tell Miles or the IRS that I’m having such a good time.

THE END (but keep reading)

*to be clear, Scott didn’t mention me, but his statement came just days after I sent him an email invite to be on my show. I don’t know if he ever read my note and I’m sure he receives dozens of podcast invitations every week, but how many are from bald comedians who wish they were Joe Rogan?

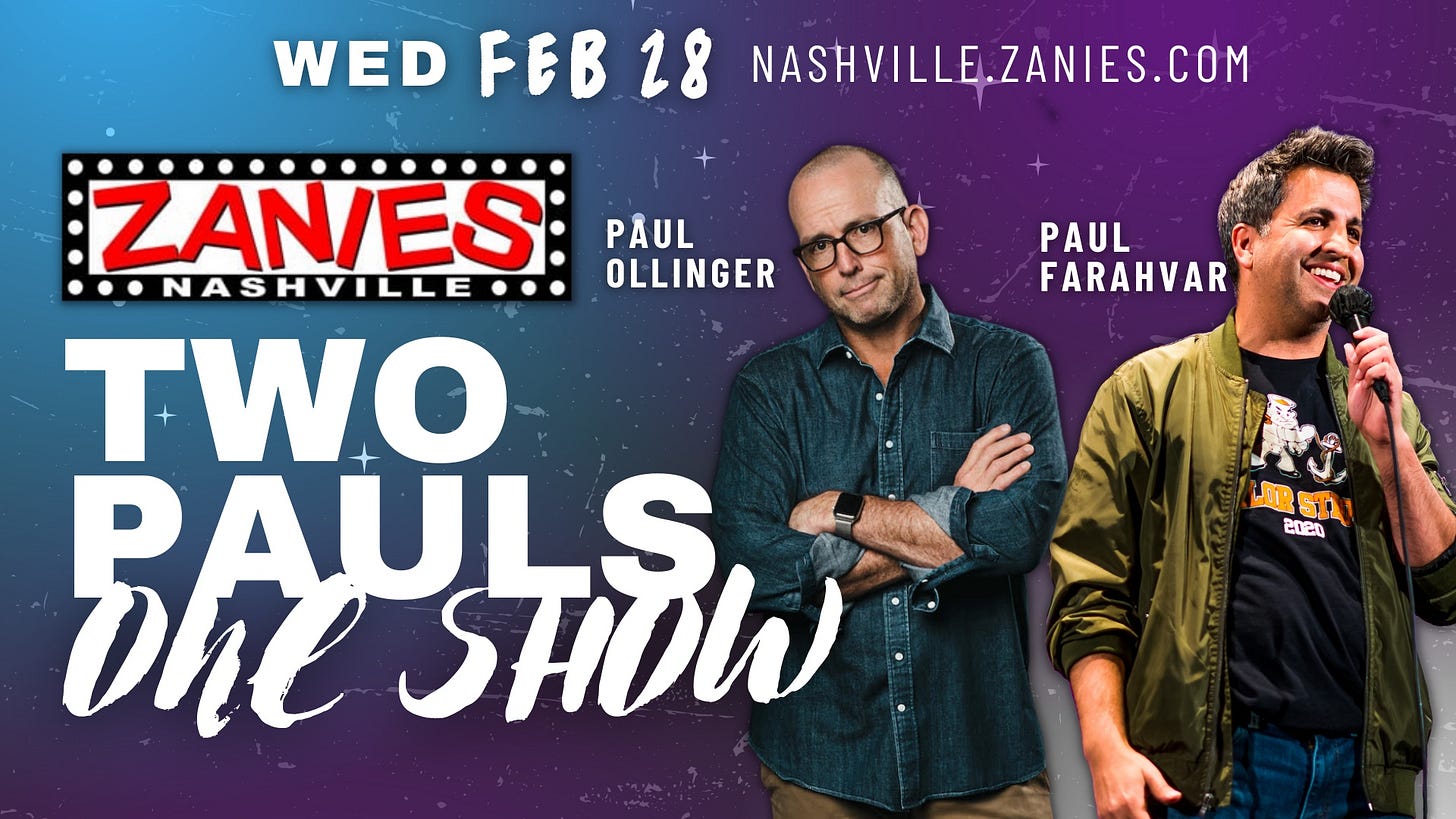

Hey, come see me tell jokes, alive and in person:

San Francisco, CA - Cobb’s Comedy Club - Feb 22: Tickets Here

Nashville, TN - Zanies - Feb 28 Tickets Here

Washington D.C. - DC Comedy Loft - 4/19-20: Tickets Here

More upcoming shows in Raleigh (okay, Cary!), Denver, and lots of country club shows in Atlanta. See the full schedule here.

Having also stumbled into a demographic group which is no longer primarily concerned with making money to survive, I'm struck by the observation that some of the most meaningful experiences of my life have been significantly subsidized by outside capital (VC, trust fund, nest egg, etc).

As a child (i.e., before I was about to turn 50), I'd always assumed that the value I paid for something was the true value of the experience. Now that I've enjoyed dozens (maybe hundreds) of VC-subsidized, "pre-revenue" services and products in the Bay Area, alongside tens of lovely restaurants that came and quickly went, and gallery exhibits which didn't sell out, it's becoming clear to me that profitability is not the only test of value (and maybe not even a good test at all).

Godspeed on your hobby/passion project/creative pursuit/meaningful work!

C-corporations are immune from the hobby loss rule. The Hobby loss rule applies to everything else - Individuals, Partnerships, Estates, Trusts,and S-Corporations.

Create a C-corp for podcasting, you can carry the Net Operating Losses forward indefinitely (due to 2017 new law) - so stack them up.

When the time comes, and you need a company to actually do something with, instead of creating a new company, refocus that company on its new purpose that is profit related, carry the losses forward to avoid income tax on the c-corp. When the company has income, you can eliminate up to 80% of your taxable income each year with losses from prior years. Or, you can have that company start doing something else in addition to your podcasting that generates income.

The C-corp can issue you dividends, which avoids payroll and income taxes, and instead is taxed at the cap gains rate, which is likely lower for you. So the money coming out is taxed very little due to the stacked NOLs and the money doesn't get all the taxes an LLC or S-Corp would once it goes to you.

This only works if you intend to have some sort of enterprise that makes money of course, or you already have one.

I know this because we had a company that lost money for quite a few years, which was a plan, because we were re-investing it back in and I got this advice from a CPA that seemed to be 100 years old. Back then you could only carry the loss forward for 20 years however.