Gary v. Jerry

Why Gary Gulman Resents Rich People

If I could choose a super-power—after X-ray vision and the ability to fly—I would choose the ability to implant in other people a faith that they can achieve and enjoy financial prosperity. Lacking this trust in economic self-determination, a person will never reach his or her full potential.

A prime example of the attitudes that limit financial success and fulfillment can be seen in Born on Third Base, the recent Max—fka “HBO”—comedy special by the transcendentally talented Gary Gulman. New York Times comedy critic Jason Zinoman called it a “meticulously funny hour that digs into the gap between the haves and have-nots.” That it is, but as someone who has been both “have” and “have not,” and who has performed thousands of stand-up comedy shows across the country, I feel strong, conflicting emotions about Gary’s message.

I grew up one of six children to parents who were scarred by the Depression and never made a lot of money. We had all we needed, but budgetary stress lingered like an irritating, omnipresent guest. I channeled that angst toward building a great corporate career, and found one that even allowed me to retire early.

Gary Gulman was born a “have not” and eventually became one of the most gifted comedians on the planet. A dedicated craftsman, he weaves jokes, observations, and wordplay into intricate tapestries of humor. His bits about non-obvious topics—grapes versus grapefruit, the origin of the 50 state abbreviations, and Hitler’s “shenanigans” have earned him a spot in the pantheon of modern, cerebral comedy.

Born on Third Base is a worthy addition to his body of work. Always vulnerable about his insecurities and struggles with mental health, Gary reflects on his impoverished youth and the indignity of free school lunch (and breakfast!). He calls bullshit on the welfare-dependency trope and makes a compelling argument that no one understands the zero-sum realities of home economics like poor kids. But he also demonstrates a crippling poverty mindset and a crushing envy of those who have more than he does.

He’s discussed this issue before. In his 2023 memoir, Misfit, Gary writes at length about his grudge against wealthy people, quoting The Great Gatsby, “I have never been able to forgive the rich for being rich and it’s colored my entire life and work.” He goes on to explain how much he hates elitist “sports” like skiing and how he sees the resulting torn ACLs and broken limbs as “cosmic judgement for their opulent f-you to the working class.”

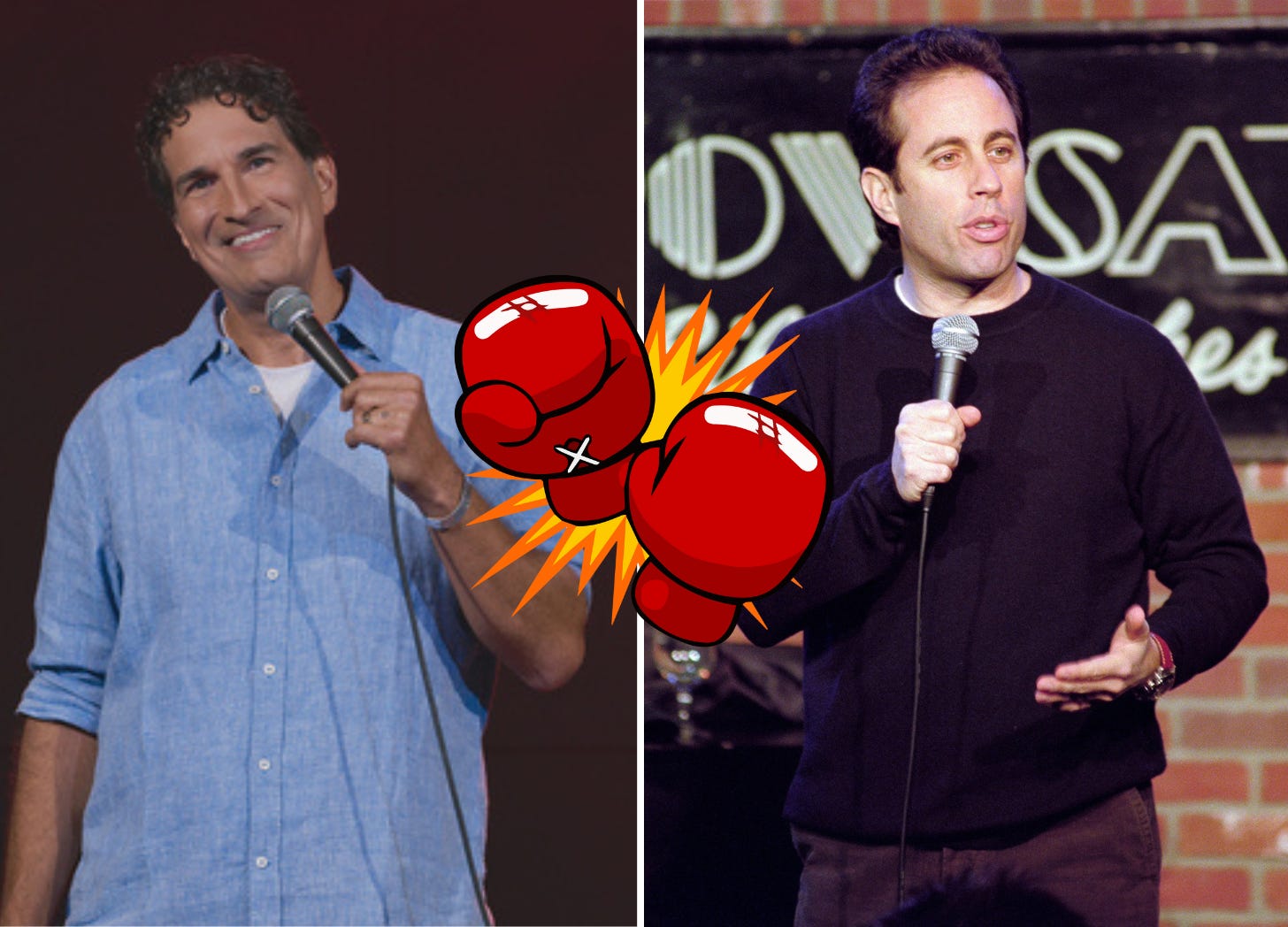

One sees this rancor coloring his work in the new special when he analyzes “cartoonish” income inequality by contrasting his financial situation with that of Jerry Seinfeld. In this “Jerry v. Gary” bit, he suggests with numerical precision that, since the two men are in the same business, there could be no justifiable reason that Jerry is a billionaire while Gary’s net worth hovers around $89,000. He wonders how it could possibly be fair that Jerry owns a building to house his Porsche collection when Gary and his wife can’t afford a 4-slice toaster.

As funny as this juxtaposition is, the logical—and perhaps, factual—errors runs deep. First, Jerry’s astronomical net worth came not from joke-telling, but from television production. If Gary wishes to close the gap between Jerry and himself, all he has to do is go back in time and co-create a sitcom so popular that 76 million people watch the finale. He could then sit back for 25 years and watch his net worth soar, propelled by re-runs, residuals, and compound interest.

But very few comedians have created such beloved touchstones of pop culture. Ray Romano probably came closest by starring in Everybody Loves Raymond and earning himself hundreds of millions, which is a lot, but still only a fraction of Jerry’s balance sheet.

Ray doesn’t seem bothered by this disparity, but Gary really takes it personally. Why? Has Jerry’s success deprived Gary of a single dollar? Of course not. In fact, one could argue that the former paved the way for the latter by proving the market for nuanced observational comedy and helping to keep open the clubs where Gary eventually learned his craft.

Speaking of that craft, one explanation of the two comics’ divergent monetary outcomes lies with their respective products. In the new special, Gary alleges that he is a better comedian than Jerry. That may or may not be true, but guess what—it doesn’t matter. While brilliance and economic success are likely correlated, massive financial windfalls in entertainment result only from mass appeal. And while Gary ostensibly speaks on behalf of the common man, he requires the crowd to meet him at intellectual heights well above that of mainstream “brutes,” as he acknowledges in Misfit. His jokes are too clever, dare I say precious—yes, I dare—for the mass audience. For better or worse, that’s where the money is.

There are a million examples of this, in every art form. Essayist George Saunders might be the most talented writer alive but he’ll never earn as much money as the person who composes the next Avengers script. Taylor Swift may not be the best guitarist in the world but she is the most popular, and that’s why she, like the guy who played “Jerry” on Seinfeld, is a billionaire.

On the surface, Gary is calling out inequality but by creating this "us vs. them" duality, he’s just perpetuating the paralyzing attitudes that will keep him and millions who share his resentment from achieving their financial potential.

Here’s another example: Gary contends that growing up poor makes a person more empathetic and offers as proof the way upper-class customers “wag their finger” at Chipotle or Subway employees. While I have no doubt many affluent people act entitled in public, whenever I see a viral video of a Burger King brawl or Waffle House fight club that started because the cashier didn’t provide extra napkins, the fist-swinging, hair-pulling customers don’t appear to be doctors, lawyers, or hedge fund managers. He’s right that the treatment of service workers is an issue of class, but only in the sense that “class” is defined by the way someone, rich or poor, demonstrates courtesy to their fellow human.

The most intriguing part about Gary’s situation is the fact that he almost certainly earns over $1 million per year. If, for example, he sells out his upcoming show at Washington D.C.’s 1,800-seat Warner Theater for a very conservative average of $75/ticket, his 50% of the gross would total about $68k. Deduct 25% for agents, managers, and travel, and he would still take home $50,000 for the evening. That buys a lot of toasters.

One million annual dollars isn’t a billion in net worth, but it places him deep into the top 1% of U.S. earners. And here’s where things get complicated. Gary’s economic reality is now at odds with his self-image and long-held animus. For a person scarred by childhood deprivation, this cognitive dissonance induces guilt and shame. To atone for the perceived sin of his accomplishment, he projects that transgression onto someone who has even more. In the process, he transmits the virus of self-limiting resentment onto a delighted audience that has no idea—or, worse, just doesn’t care—that they’re infected.

Gary’s comedy has given me a lot of joy over the years and he has earned all of his artistic and financial success. I wish I could give him the power to enjoy it. Because welfare might not keep people poor, but negative beliefs sure do.

THE END (but keep reading…)

See Paul live in comedy mode:

San Francisco, CA - Cobb’s Comedy Club - Feb 22: Tickets Here

Nashville, TN - Zanies - Feb 28 Tickets Here

Washington D.C. - DC Comedy Loft - 4/19-20: Tickets Here

More upcoming shows in Raleigh, Denver, New Orleans, and lots of country club shows in Atlanta. See the full schedule here.

Seinfeld's grandparents sold fish from a push-cart to make it here, like many they came here to Ellis Island with nothing - they couldn't even afford a radio. His dad was a working-class sign painter, and his mom was unemployed. Jerry did not have privilege - he worked multiple jobs and took out loans to pay for his college at a state school.

.

Gulman however, got a full scholarship to Boston College - a more expensive private university- for playing football, and after getting his accounting degree there got a rather good job at a big-six consulting firm - I'm sure he made a lot more than Seinfeld at that point in both of their respective timelines, as when Seinfeld was that age he was making virtually nothing doing open-mics and stand-up at small venues.

.

All this is to say, to me, Gulman's growing up poor didn't hurt him at all - except maybe his mindset. Zero-sum thinking is poison.

Thanks for posting! I agree with you. I'm following you because I find your writing and podcasts funny, and as a bonus, they highlight stuff that needs highlighting, and do it in a way that doesn't demonize. I like the LouisCK and Rodney Dangerfield examples for the same reason. LouisCK's clip below especially "you're taking my money because I don't have enough money!?"