Data Privacy is an Illusion

The Evolution of Ad Tech and Erectile Dysfunction

**TMI Warning: This post addresses subjects some might find uncomfortable. (But at least it’s not political!)**

Around 2005, the general manager of a Minneapolis Target store caught an earful from the father of a teenage girl to whom the retail giant had sent coupons for infant clothing, cribs, and other baby gear.

“It’s wrong to send these to a high school student!” vented the vociferous dad.

But guess what – by applying predictive analytics to the daughter’s purchase history, Target’s marketing department had diagnosed her condition accurately. (She was totally preggers.) It is an eye-opening anecdote about the power of corporations to see into the most intimate aspects of their customers’ lives from a time when data tools were relatively primitive.

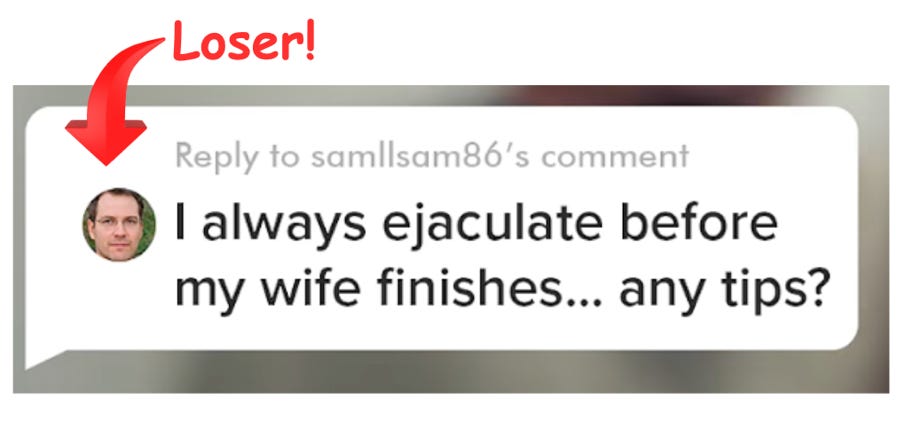

I’ve been thinking about this lately because the advertising I’m seeing on Instagram is jarringly specific. Based on these ads, the social media platform appears convinced that I am:

Shopping for a new down vest

Exploring country clubs to join in the greater NYC Area

Struggling with a chronic tendency to ejaculate prematurely

I promise I didn’t make this up because I thought it would be funny. But let’s assume that at least two out of three are true.

I’m not going to say which is which, but the META ad server isn’t taking any chances. So, it jams my feeds with ads for over-priced outerwear, golf courses, and online pharmacies featuring shamed men, unsatisfied women, and eye-catching copy like “Ejaculating too early SUCKS.”

On the one hand, it’s a little shocking. On the other, it demonstrates how far online advertising has come—no pun intended—in the past two decades.

When I sold digital media at Yahoo! c. 2001, we offered “run of site” ads. This meant banner ads were served at random to whomever loaded a page, regardless of the user’s identity. Men saw ads for Tampax, women saw ads for Viagra, and the inefficiency was reflected in a lower cost (CPM) charged to the advertiser.

For marketers who wanted to reach male baseball fans or active investors, we could focus on our Sports or Finance properties. But we had no way to target a person’s gender, age, or proclivity to orgasm long before his partner realized he was inside of her. (Or, in 4-5% of cases, him.)

Eventually, the technology improved and Yahoo! began requiring users to share more data, such as name, age, and geography. Never to my knowledge, however, did it inquire as to that person’s average duration of lovemaking before apologizing and slinking off to the bathroom.

Facebook’s arrival in 2005 took things to a whole new level. It started with registrants’ real names and colleges, but could also identify users’ friends and relatives. The burgeoning platform eventually integrated data from cookies, search history, and third-party sources (credit card purchases, vehicle registration, credit scores, etc.) to create one of the largest and, let’s be honest, scariest databases in history, containing billions of humans’ demographics, psychographics, and—apparently—degrees of flaccidity.

Facebook segmented this audience into myriad target buckets, indicating that those therein are, for example, an avid reader, in the market for a premium SUV, or the kind of guy who has to do long division in his head to maintain an erection longer than 45 seconds.

Today, META properties can target alleged premature ejaculators in many ways, including, but not limited to:

Demographics: Men, 45+ years old

Look Alike: Users who demonstrate the same characteristics as a list of the advertisers’ best customers.

Behavioral: Guys who recently Googled “Kegel exercises” or “why does my wife cry after we have sex?”

So even if I’m not guilty of early accelerated release, they’ll still serve me the ad. But the moment I click on it—even if I absolutely do not need their silly product but just happen to be curious—they double down and blast their message to me.

If all this sounds like a violation of privacy, you obviously didn’t read the 57 pages of 6-point Helvetica in the META User Agreement. Besides, resistance is futile. There are simply no secrets in our mobile, digital, connected world.

20 years after a Target statistician using Lotus 1-2-3 and a slide rule determined that a Minnesota teenager was with child, those same prognosticators leverage the nuclear, predictive power of AI to understand who we are and how we’ll act in the future! Verizon knows if and with whom you’ll have an affair. American Express knows you’re on your way to developing an alcohol problem. And Google knows you will soon be addicted to YouTube videos about in-ear blackhead extraction. (Please - do not Google it!)

There are costs and benefits to this world we now live in. On one hand, it’s amazing that we can tell our phones we’re hungry and have a smoothie delivered 20 minutes later.

On the other hand, I really miss seeing Tampax ads.

THE END (but keep reading ↓↓↓)

Real quick - two things:

I’ll be headlining Denver Comedy Lounge October 17 - 18. Tell your Denver friends to get tickets here.

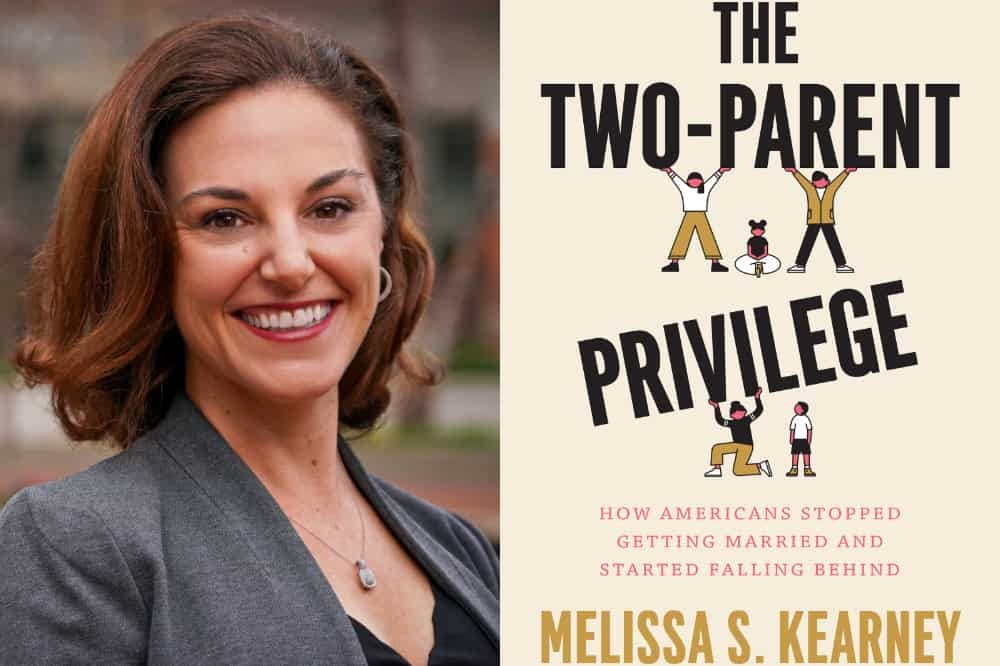

You need to listen to this week’s encore podcast episode with Notre Dame economist Melissa Kearney, author of The Two Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind. Melissa has spent her career studying poverty, government policy and inequality, so she cares about helping people achieve economic autonomy. But there’s one important factor that most academics are unwilling to acknowledge: family structure matters. Listen here.

Carpe Diem!

26 years ago, my wife got an early sonogram because a slight uptick in a blood test indicated she might be carrying twins. This was just two weeks after we knew she was pregnant. The sonogram showed two little eggs so we knew we would be having twins many months before the birth. 3 weeks after getting the sonogram, we started getting catalogs in the mail that were TWIN themed catalogs for baby stuff. This issue of privacy is not a new issue.